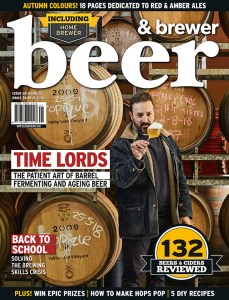

The cover feature of our recently released Autumn magazine showcases the “Time Lords” of Australian brewing who are mastering the patient art of barrel fermenting and ageing beer. Adam Carswell chatted with La Sirène’s Costa Nikias (pictured above and on the cover © Henry Trumble), Future Mountain’s Ian Jones, Dollar Bill’s Ed Nolle, Wolf of the Willows’ Josh Kendal and US brewery Founders’ Jeremy Kosmicki to discover the challenges and the rewards of this centuries old endeavour. For your enjoyment we’ve reproduced that feature here.

Some people just like to take their time.

In an everchanging industry, that feels like it’s travelling at break-neck speed with oodles of new releases hitting the shops weekly, a growing number of brewers have become inclined to take a more considered approach while gathering a bunch of plaudits along the way.

Craft beer makers Future Mountain Brewing and Blending (winner of four gold medals and the Champion Brewpub and Champion Victorian Brewery at last year’s Independent Beer Awards), La Sirène Brewing (whose Saison has been described as one of the best Australian beers of the past decade) and Dollar Bill Brewing (winner of the Champion Australian Beer trophy at the 2021 Australian International Beer Awards) are cases in point.

For different reasons, they’ve all based their successful operations almost entirely on the slow and steady technique of putting beer in barrels.

Barrel fermenting and barrel ageing beer (two distinct processes, mind you) are not for the impatient or faint hearted, but the ensuing results lean towards spectacular and complex.

Future Mountain’s Ian Jones explained that he and co-founder Shane Ferguson were both commercial brewers working in Melbourne before embarking on their own project.

“We both have a passion for farmhouse ales, mixed fermentation, barrel aged beers, Saisons and American sour beers,” he said. “We were always going to open a brewery with the majority being fermented in oak.”

La Sirène’s Costa Nikias recalled starting out with half a dozen 225 litre barrels as “sort of an experiment to see what would happen”, at a time when “very few breweries, if any, were using barrels to ferment and mature beer in”.

“Fast forward 10 years, we now have over 250 barrels and a bunch of 500 litre puncheons, foeders et cetera… So I guess you could say the experiment has somewhat consumed us ever since,” he said. “It’s (been) very intriguing to attempt to understand all the symbiotic reactions that may be happening in every one of those barrels.”

As relative newcomers to the field, Dollar Bill’s Ed Nolle with wife Fiona embarked on a fact-finding mission around Belgium and Northern France before their endeavour began.

“We visited as many breweries as we possibly could – Cantillon, Brouwerij Alvine, De Dolle, Half Man Brewery, there were tonnes – and had a look at how they were (doing things),” Ed said. “You get a little bit of information from each one and you kind of piece it together, and then you go and stuff it up, and you learn not to do it that way!

“(After that) I had a friend who was a winemaker. We were pilot brewing in the winery where we obviously had access to barrels. We had some great success putting stuff into (them) and letting it go sour.

“It was a little bit of that, and a little bit of the fact that I didn’t have to go and invest in thousands of dollars of stainless steel to get up and running. Easier to do, and cheaper.”

“Because we test so frequently, we can pick up if something’s going in the wrong direction. It’s our livelihood. We need it to be great every time.”

Ian Jones, Future Mountain

The dark arts

Sounds like a walk in the park? Beer. Barrel. Beer in barrel. Voila!

Well, not exactly. There’s a lot going on within these specially chosen and lovingly prepared containers, where timing is subjective, and issues swift to arise, but arduous to solve.

Ian was at pains to point out that it isn’t just “chuck a beer in a barrel and leave it for two years and hope for the best”.

“That’s so far away from what we do,” he said. “The barrels, first of all, are treated really, really well. Each has its own mixed culture, and we just keep pulling samples weekly to make sure it’s all tracking in the right direction.

“(After that) we blend from our 500 litre puncheons. We top up with specially designed beer that will aid the slow fermentation, but also won’t put the barrel in jeopardy.

“Because we test so frequently, we can pick up if something’s going in the wrong direction. It’s our livelihood. We need it to be great every time.”

As far as Ian is concerned “it’s still a fermentation – it’s a pretty complex fermentation – but like with a pale ale you measure until it’s done, until it tastes good”.

“Each mixed culture has its own life cycles,” he explained. “Then there is maturation time that we leave it (for) as well. So it could be finished fermentation, but still, some bacteria hasn’t dropped.

“You could have only one or two points left, but (even then) you can pick up some kind of character. The culture isn’t quite there yet, so the Brett (Brettanomyces) will keep going for three (or) four months.

“From taking the beer out of the barrel, to blending, to packaging, there’s still another two months beyond that,” Ian added. “The blend always tastes great, (but) then it will go through another fermentation. We have large conditioning rooms that are constantly set to 20 degrees, (so) they’ll go in there and spend around eight weeks.”

Costa said La Sirène steers away from what most breweries do to achieve the flavour profile they’re targeting, which he describes as “employing temperature control for their barrels due to various known cultures that have specific temperature tolerances and ranges”.

“In our case, no, we do not have, or want, temperature control for our barrels. We want the seasons, and in particular Melbourne’s flux climatic influences on a daily basis, to play a major part in creating (our) wild ales,” he said. “In terms of sampling, we typically taste the barrels after six months minimum. In fact I prefer not to taste them until 12 months after.

“I recall in the early days tasting them weekly and it would send me into an emotional spin as to what may have been taking place.”

He said in regards to when the beer may be “ready”, rather than prodding and probing, “it’s really about tasting it and smelling it to see if it has any more stories to tell”.

“I am a firm believer that a barrel brewer’s best tools are their nose and mouth,” he said.

“Rather than making a big batch of something that tastes kind of weird, (we prefer to) add just a little bit of weirdness to it, which adds just a little bit of intrigue or interest.”

Ed Nolle, Dollar Bill

Ed takes a simple approach at the get go, which is to find a barrel “that’s not going to leak”.

“Then we’ll just basically put our fresh wort in there and inoculate it,” he said. “We tend to do a lot of different things in our barrels, and then build (our) blend stock up so we can introduce interesting flavour components in little portions.

“That is, rather than making a big batch of something that tastes kind of weird, (we prefer to) add just a little bit of weirdness to it, which adds just a little bit of intrigue or interest.

“There’s lots of different ways you can do it. I think the industry is still kind of coming to terms with what the best way to do that is, and how it works best.”

Ed agreed, that while there’s no steadfast timeframe, knowledge he’s pruned from the Belgians is that “when they’re doing Lambics and pure wild fermentation, they recommend two Summers, so basically, two fluctuations of temperature profiles”.

“(Fluctuations) affect how the yeast actually behaves and processes the carbohydrates or fermentable sugars,” he explained. “So, ideally, two years, which is two Summers. But we’ve had some wild ferments just rip through in about six months and they come out beautiful – crystal clear and ready to go. The flavour profile is fantastic.

“I typically check them every six months, (but) you’re constantly managing them because they do evaporate. They’re reducing more and more each month, so you’ve got to top them up.

“Then you’re stressing about ‘what the hell am I gonna put in there to top up something if I’m (already) getting a really good profile out of it?’ If you’re introducing all these other yeasts and bacteria into it, how’s that going to react and behave?”

To the source

There’s barrels and then there’s barrels.

Speak to any brewer with a barrel program and they’ll tell you the biggest bugbear they have, especially early on, is sourcing a constant supply of decent ones.

For Josh Kendal (pictured above, on the far right), head brewer at Wolf of the Willows in Melbourne’s south eastern suburbs, it’s all about creating “relationships with likeminded small businesses”.

“We are very lucky to have such a great relationship with Australian spirit producers such as our friends at Lark Distillery in Tasmania, and The Gospel Whiskey and Patient Wolf Gin here in Melbourne,” he said. “The barrels we receive from Lark, Gospel and Patient Wolf are of the highest quality – not only with the barrel integrity but also the flavours they produce.

“Most often and most preferably we receive them fresh and soaking in whiskey, or gin in Patient Wolf’s case. This keeps the wood moist and ensures sterility, not to mention fuller flavour carry-over of the spirit.

“As for Lark in particular, many of these barrels are returned and again used to age whiskey for a special release that coincides with our Imperial Johnny Smoke Porter. We do a similar thing with Patient Wolf Gin, however on a much smaller scale.”

For the aspirational home brewer

If you’re contemplating having a crack yourself, once you get your mitts on a suitable barrel, achieving something drink worthy is definitely possible.

“It’s hard as a home brewer because (with) the smaller barrels, there’s a lot of oak contact there so it’d be a pretty short turnaround,” Ian advised. “If you’ve got your hands on a wine barrel (especially), you need to make sure that it’s clean before you put anything in it – to start from zero as in culture wise. Plus look for any holes. They’re the main things.

“It’s (all about) keeping an eye on it, monitoring it. Make sure you put a healthy mixed culture pitch in there, so you haven’t got wort sitting in a porous vessel potentially getting contaminated for a long period of time. You want to get that fermentation happening so it can outcompete anything in the oak.”

“Even 10 years in I do not feel I understand much. I’m beginning to think we won’t work it out in my lifetime.”

Costa Nikias, La Sirène

Costa cautioned that mistakes are bound to happen.

“If you want to play with barrels, and rely on your environment to influence (them) creatively, in your mind you need to be prepared to dump around 30 percent of your stocks annually,” he said. “What we have learnt over the years are the little tricks to help guide and steer a fermentation in the right direction, to minimise the need to start again.

“So, number one, be prepared to dump (a percentage) of what you age in barrels. Number two, have fun and try new things, as the feedback will guide your learning. Number three, be patient – these things take years to begin to understand. Even 10 years in I do not feel I understand much. I’m beginning to think we won’t work it out in my lifetime.

Ed pointed out: “If you’re going down the barrel route, there are some smaller barrels (you can find – for example). 225 litres is fine to play around with if you’ve got the area to store it.

“I’d probably try to avoid stuff that doesn’t smell nice. You (also) want to keep it fairly stable temperature-wise, you want to keep it topped up, and (again), you probably don’t want to get anything that smells bad. If it’s got a bit of mould and it smells okay, it’s probably alright to use. But if it’s got a bit of mould and it smells bad, don’t use it.”

Underground lovers

Looking towards the upper mid-west of the US, Michigan’s sometimes controversial Founders Brewing Company’s barrel-aged series is the stuff of legend.

It’s a constantly evolving line-up, with the recent roll call including the cult favourite Kentucky Breakfast Stout (KBS) – a 12.0%, 45 IBU imperial stout brewed with coffee and chocolate and aged in bourbon barrels; Frootwood – an 8.0%, 15 IBU cherry ale aged in maple syrup bourbon barrels; and MAS Agave Clasica Lime – a 10.0%, 15 IBU barrel aged imperial lime gose.

What’s even more remarkable than the diversity of brewmaster Jeremy Kosmicki’s program is where the ageing actually takes place – in a cave almost 30 metres below terra firma, which houses up to 6,000 barrels at a time!

“We didn’t have much storage space at the original brewery, especially cold storage,” Jeremy said. “The (former) gypsum mines offered a huge amount of storage that was temperature and humidity controlled, and allowed us frequent access for sampling since they are local (to Grand Rapids).”

In terms of planned yearly releases, Jeremy said there’s no set number. KBS and Backwoods (Scotch ale) are year-round, after which he tries to work in a combination of “new experiments and some classic repeats”.

“The beers that we’ve been making repeatedly are pretty dialled in and don’t need much monitoring. (However), if it’s a new project, or especially a new type of barrel, we’ll want to sample them every couple of months and see how they’re doing. Once the flavour stops progressing, we’ll empty them.

“It’s been a lot of trial and error over the years but it’s pretty rare that something just doesn’t work. I certainly consider what character the particular spirit (barrel) is known for, and then think about what types of beer ingredients I can use to work alongside those flavours.”

Barrels of fun

With all the work and waiting involved, you’d have to reckon that when a barrelled beauty is finally done, the suspense within the brewhouse would be as thick as molasses.

It’s a point perfectly put forth by Ian.

“The exciting bit is when you can walk in there (the conditioning room), grab one, and it’s tasting great.

“But we’ve been here three and a half years with beer in barrels for (all that time), and everything’s so young still. It’s still building, and the cellar isn’t even close to being mature.

“The mixed cultures that we have in here are still a bit finicky. They cause a bit of stress sometimes, because they haven’t really settled in yet. We’re looking at a 10-year project to get these barrels performing as we’d like them.”

Ed (pictured above with Fiona) said it’s “probably more nerve wracking than exciting” towards the end of his own process.

“Trying to make something out of each 200 litre barrel into a commercial quantity, it can be quite difficult,” he said. “You chuck fruit in there (for example), then you’ve got to carbonate it, you’re putting them into a bottle.

“Then the bacteria that’s still live in there will probably jump on that dextrose and throw off all these other flavours, so you’ve got to wait until that settles down again. Round and round we go!”

Costa agreed.

“It can be exciting and a little daunting at the same time. Only because you don’t know what it will end up like.

“It’s our illusion of control of a situation that creates that anxiety. Once you realise it’s always transient and changing, you begin to go with the flow and take it as it comes. That’s how I’ve framed it in my mind anyways.”

This feature appears in our recently released Autumn 2022 edition. To see it in print, and to read more features like it, subscribe to our quarterly magazine for as little as $29.50 a year.