In honour of the best day of the year, we’ve gone back to basics with a little refresher course on just what is beer….

So What is Beer?

Beer is the most popular alcoholic drink globally and is the third largest consumed beverage in the world, behind water and tea.

The Oxford Dictionary’s definition of beer is “an alcoholic drink made from yeast-fermented malt, flavoured with hops”. In truth, beer is much more complex than this definition and difficult to define in exact terms; for every general assumption or definition made for beer, there is invariably a beer style or varietal which contradicts the rule.

Beer can best be described as an alcoholic beverage produced from the fermentation of sugars primarily obtained from the starch found in grain. The starch sugars are most commonly derived from cereal grains, especially barley and often include wheat, rice, corn, rye and others. More complex sugars known as dextrins, which do not readily ferment into alcohol, are described as residual sugars, remaining in the brew creating the intensity and sweetness present in the beer.

Fermentation is most commonly conducted by yeasts, a whole family of single-celled creatures whose mission is to convert sugars to alcohol and a panoply of other beery flavours. Other more complex fermentations can also be conducted by micro-organisms such as bacteria, as is the case in Lambic-style beers, and barrel inoculated ferments.

Hops are added to most beers and can be used for a combination of bitterness, aroma and preserving qualities. In the absence of hops there are native plants, herbs and spices the world over which can aptly substitute.

As beer is produced from agricultural products the consistency of the raw materials varies with the seasons, adding to the brewers’ art of consistently replicating each brew by juggling the quantity and concentration of ingredients. Other styles, however, may benefit from embracing this cyclical change.

Beers are classified into styles and appraised through appearance, aroma and taste. Some beer characteristics which help to enhance the identification and description of beers include alcohol content, colour, bitterness, flavour profile, ageing, storing, package type, malt treatments (such as smoking and roasting) and use of non-malt adjuncts.

Steeped in history, beer has traditional classifications as well as modern expressions and interpretations of style, each adding to the interest, complexity and variety of beers, crafted, created and commercialised by the brewers themselves.

To better understand beer – to know the various attributes, explore the different characteristics and appreciate the abundance of styles – it is worth sampling an array of beers, as seen in this book’s Style Notes section, as it is a great way of combining academic beer appraisal with your own sensory evaluation and makes for a good knowledge reference point.

After that, beer is your ocean. Enjoy.

Ale

Genus – Saccharomyces Cerevisiae

The ale yeast is a different beast. These types of yeast would have been used from nature for the earliest beers. It is a rather more delicate chap desiring warmth (13-26°C), and it causes much more fuss while going about its work, producing all sorts of aromatic and fruity aromas, and giving up the ghost far earlier during its sugar-eating task. And once it has done its work, the yeast floats to the top of the brewing vessel forming thick pillowy crusts, giving it the term ‘top-cropping’ or ‘top-fermenting’ yeast.

These beers are fuller-bodied, fruity and rounded, producing yeast aromas that have great character in their own right, which wrap themselves around and accentuate malt and hop character. They are, of course, ales.

Lager

Genus – Saccharomyces Pastorianus

This strain of yeast evolved in the cold caves of Bavaria over many centuries where, after a busy winter and spring brewing season, beer was stored throughout the warm summer. It acclimatised and thrived in low temperatures, slowly improving and developing the stored beer – a process we now call lagering. Lager yeasts like things cool, fermenting happily at low temperatures (1-14°C). They work cleanly and with little fuss, producing only delicate flavours and working until a goodly portion of the present sugar is gone. When it runs out of sugar, it falls to the bottom of the tank where it can be cropped for the next brew – giving it the term ‘bottom-cropping’ or ‘bottom fermenting yeast’.

The resulting beers are dry, crisp and delicate allowing malt and hop flavours to come to the fore. A perfect, if broad, description of a lager.

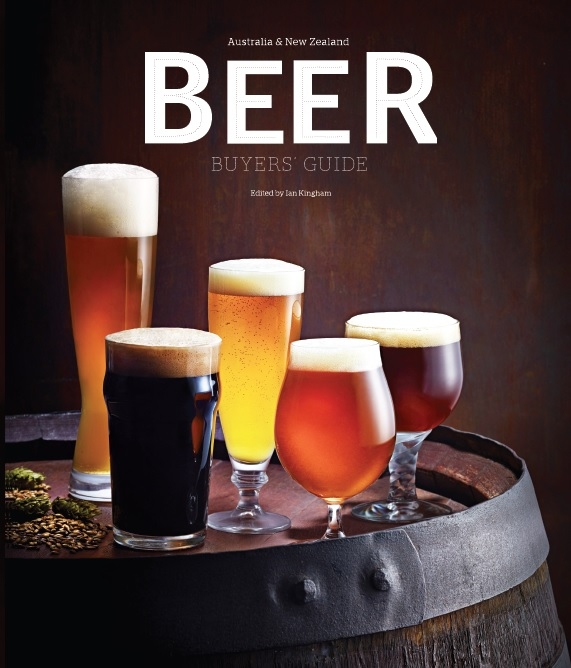

Get all this information and loads more in the soon to be released Australia & New Zealand Beer Buyers Guide from Beer & Brewer.