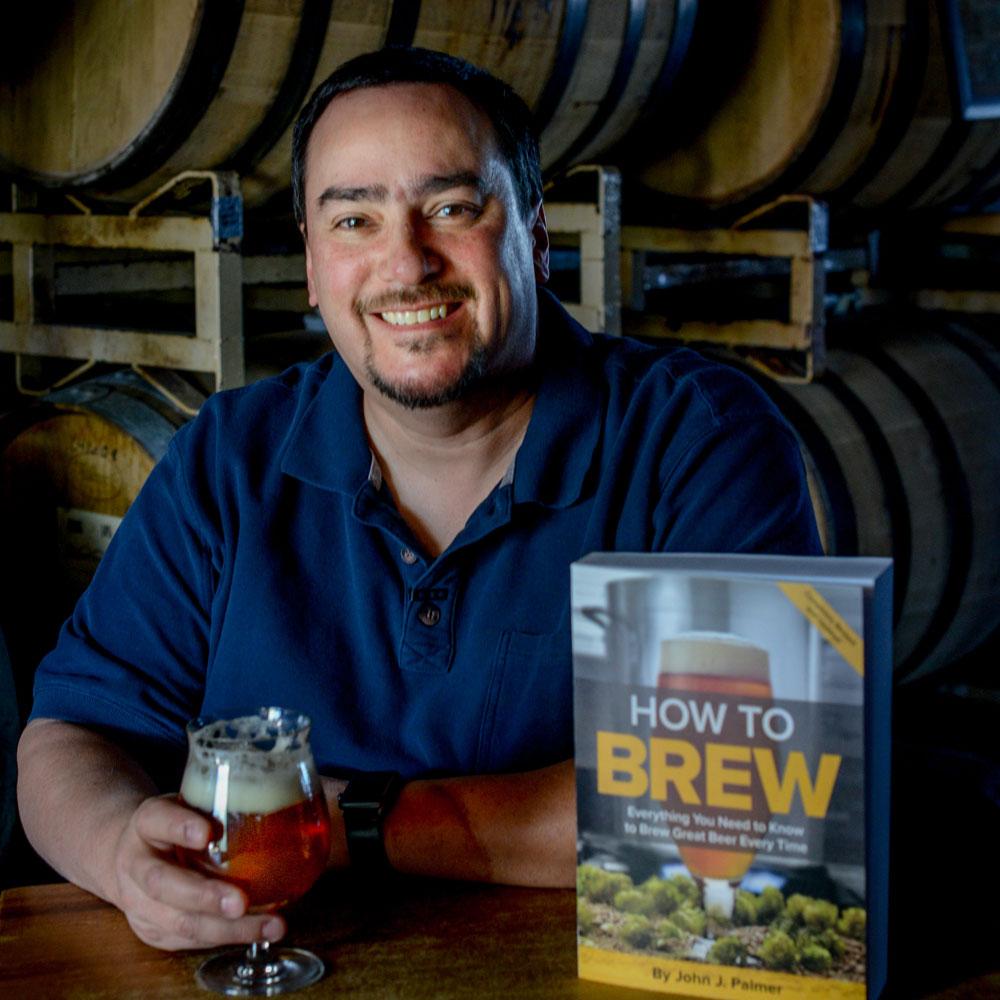

Home brew guru John Palmer – the author of the bestselling How to Brew – guides you through aspects of the art of brewing better kettle sours and then dishes up a recipe for one of his favourite styles. His Zilwaukee Bridge Bruin is a departure from his Tittabawasee Brown Ale in How to Brew and is named after a concrete bridge further downstream as it goes past Saginaw Metal Castings Operations of General Motors in Michigan. In every issue of Beer & Brewer John dives deep into a particular facet of brewing better beer and regularly provides one of his recipes. Subscribe to the magazine here.

It’s fascinating to me how quickly kettle sours have become mainstream for so many home brewers! I used to think sour beers were for the elite, the daring and the sagacious! For those of you who have never done a kettle sour, the process is fairly simple:

- Mash and lauter (or BIAB) your grist as usual.

- Bring the wort to a boil for 5 to 10 minutes to kill off unwanted souring bacteria that may have survived the mash. Do not add hops.

- Chill the wort to 38 to 43°C. Room temperature will also work, but it works better warmer.

- Pitch your bacteria culture to the kettle.

- Allow the wort to sour for 24 hours. Try to maintain the 35 to 40°C temperature.

- When the wort has reached the desired sourness (pH), resume normal brewing operations (bring it to a boil and do your hop additions).

Hitting a sour note

Of course, there are several considerations that need to be understood with the kettle souring process, but overall, it is not complicated. The short boil is an optional step for many brewers, but unless you have done the same recipe and the same procedure several times, I would not recommend skipping it. The short boil ensures that the wort is thoroughly pasteurised and that no Enterobacter-type bacteria have survived the mash to make your kettle sour smell like vomit. If you had performed a mash out step with recirculation, then that would probably be sufficient and you could skip the short boil.

Cooling the wort to the recommended pitching range is also recommended. Maintaining that temperature (around 35°C) is also recommended but may require a heating blanket. Room temperature would work, but the growth and resulting acidification would be slower. In How to Brew Chapter 14 Brewing Sour Beers, I recommend pre-acidifying the wort with off-the-shelf lactic acid to discourage wild bacterial growth and inhibit protease degradation of the foam proteins. If you can pitch a sufficient amount of lactobacillus, then you will most likely achieve your sourness level (3.2-3.8 pH) in 24 hours and the foam proteins will be mostly unaffected. A lower pitching rate, or cooler souring temperature could slow the souring to 48 hours (for example) and that could result in head retention loss. Pre-acidification is belt and suspenders and is probably not needed – especially if you do the short boil.

The general rule of thumb for yeast pitching rates will work for bacteria for kettle souring i.e. one billion cells per litre per degree Plato. (1°Plato = 4 gravity points). However, lower pitching rates (0.2 to 0.5 billion per litre per °P) work just as well and save you some money. You don’t need to pitch as much bacteria as you do yeast because they don’t eat very much – about three gravity points (0.003).

You are generally targeting a soured pH of 3.2 to 3.8 and (this is important) you need to measure this with a digital pH meter, not pH test strips! I’m sorry, but they are just not reliable when it comes to measuring wort and beer. After the wort has soured, you can bring it back to a boil and continue with the recipe. The last consideration is that the lower pH is more stressful on the yeast and therefore the fermentation of the beer benefits from a higher yeast pitching rate, generally 33 per cent more than you would normally use. This should be sufficient.

John responds to a reader’s letter

Warwick asked: “I’m a home brewer with a basic kit. I’ve recently been trying to brew some kettle sours with mixed results using lactic acid to acidify the wort, IBS support tablets to produce the lactic acid before re-boiling and fermenting out. Recently I tried the Philly Sour yeast from Lallemand and this was a game changer. To only use one yeast for fermenting and lactic acid production was much easier and I was able to hit a lower pH as well. Importantly, the end product was fantastic and the yeast seemed to thrive on the fruit additions. The only issue was that due to not running a kegging system I had to use a killer yeast for bottle conditioning to prevent the risk of bottle explosions. Do you think this yeast, and yeasts of it’s type, will revolutionise the brewing of sours for both the home brewer and commercial brewer?”

Lallemand SourPhilly is a Lanchancea thermotolerens strain, which is a different genus than Saccharomyces cerevisiae beer, wine, and baking yeasts. Lanchancea is readily found in nature and is a typical constituent of natural (ie. not inoculated) wine fermentations. Thermotolerens is a unique species of Lanchanea that also produces lactic acid as it ferments. It is not a strong yeast, at least when compared with cerevisiae.

As a manufacturer, it is hard to predict how people will use your product, and be able to guarantee good results. Thus, for best, most consistent results, Lallemand doesn’t recommend priming and bottle conditioning with this yeast. It would probably work, most of the time, but there is a significant chance that a primed beer would not fully carbonate. In addition, there is a variant of this species that expresses a diastatic enzyme that could result in breakdown of normally unfermentable dextrins and over pressurisation. Therefore, Lallemand recommends the use of a Saccharomyces yeast for bottle conditioning. This could be any robust ale or lager yeast that you would find at your local brew shop. Saccharomyces will outcompete or actually suppress the growth of Lachancea (this is the “killer” aspect) by secreting polypeptides that create holes in the cell membranes of other yeast species or genus. It is actually why fermentation by S. cerevisiae, as we have known it in both brewing and baking, has been so successful for millennia.

The bottom line is that Lachancea will produce a very tasty sour beer without the need for the delayed brew kettle souring process. This yeast genus is known for fresh fruit flavours and aromas like peach and apple. Do I think it will revolutionise brewing sours at home and commercially? Maybe. Like the Kveik yeast strains, it certainly is a game changer. Currently there is only this particular strain of it, as opposed to a dozen different strains of Kveik on the market, but with time I think we will see more.

Zilwaukee Bridge Bruin All Grain/BIAB Recipe

(expected figures)

OG: 1.060

FG: 1.014

ABV: 5.5%

IBU: 30

Volume: 23 litres

Ingredients

4.5kg Pale Ale malt

500g Simpsons Brown malt (400L)

500g Caramel malt (80L)

150g Roasted barley

20g Ella hop pellets

Lallemand Philly Sour yeast

Recommended water profile

Ca2 50-100, Mg2 20, TA 75-125, SO42 50-100, Cl- 50-100, RA 50-100

Method

1. Heat 30 litres to 72°C. You are shooting for a mash temperature of 67°C.

2. Immerse the grain bag in the water and stir the grist to ensure it is fully wetted.

3. Mash with occasional stirring for 1 hour.

4. Lift the grain bag out of the kettle and allow to drain. You should have 27 litres of 1.050 wort.

5. Add the hops and boil the wort for 60 minutes (to 23 litres).

6. Chill the wort to 20°C and pitch the yeast. Allow two weeks for fermentation.

7. Keg or bottle. If priming and bottling, use one package of rehydrated, dry ale yeast that has good alcohol tolerance.