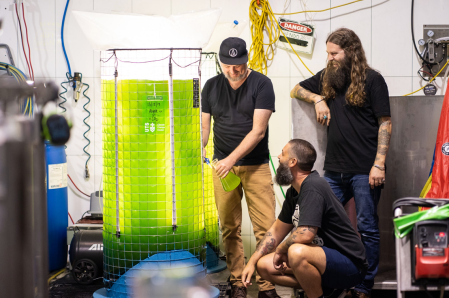

Inner West brewer Young Henrys has installed two 400 litre bioreactors into its brewery to turn its waste CO2 into oxygen.

Each glowing bioreactor takes up about one square metre and is filled with roughly 5 million microalgae celling, tiny microscopic plants that can grow in both fresh and saltwater.

Research has discovered that the photosynthesis of algae is so effective that algae actually produces more than 50% of the world’s oxygen. Additionally, the algae that is grown using the CO2 that it absorbs can go on to be used in a variety of products such as food and bioplastics.

Young Henrys co-founder Richard Adamson met some of the scientists from the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) Climate Change Cluster (C3) around 18 months ago.

They have since been working together to find ways to make brewing a more carbon neutral process. At present, the CO2 from the fermentation of one six pack of beer takes a tree two full days to absorb.

“I kind of stumbled across the idea of using some of the CO2 that we generate to accelerate the growth of algae,” Adamson tells Beer & Brewer. “We started a research project. We’re probably one year into what is a two to three-year project.

“The lab and brewery, once I got them over the fact that there’d be this big, green, glowing thing in the middle of the brewery, they got pretty excited by the whole concept.

“We’re just wrapping up the first phase of the research project with UTS and we’re working on the second phase in terms of the outcomes that we’re after, so hopefully we can get to a stage where we’ve got something wrapped up by the middle of next year. That would be our aim.”

Adamson tells Beer & Brewer that maintaining the algae is rather similar to managing yeast, except in reverse.

“Rather than taking in oxygen and sugar and then producing alcohol and CO2, it takes it CO2 and light and produces its own sugar to grow, and outputs oxygen. So it’s a very interesting product to be thinking about.

“Some of the skills we have as brewers managing yeast have an analogue in growing algae – it’s almost like they have an inverse relationship.”

The bioreactors are not just about reducing the amount of CO2 that Young Henrys produces during the brewing process, but pumping oxygen back into the atmosphere – one bag of algae produces the same amount of oxygen as a hectare of bushland.

“We’re producing more oxygen than if the entire brewery site was a forest,” adds Adamson. “Which is kind of cool, but it’s then about multiplying it and then having an application for the algae.”

In addition, Young Henrys and C3 are investigating “real world” uses for the algae itself.

“There’s a ton of applications for them,” continues Adamson. “It could be as simple as wastewater treatment or it could be as complex as pharmaceuticals. It just really depends on how it’s going to fit into what we’re doing at the brewery.”

Once the methodology and application have been finalised, Adamson is keen to encourage other breweries to “pick up and run with it”, further reducing the industry’s carbon footprint.

“The more that we as an industry can do, we could enter the stage where we’re carbon negative, where we’re capturing more CO2 than we’re outputting in the entire process. Which would be awesome.”

The project is part funded by an Innovations and Connections government grant. The first phase of the partnership between UTS and Young Henrys is the research and set up of the algae in the brewery.

The second phase, which has yet to launch, will be a long process with the hope to achieve more carbon capture to create a large biomass of algae.

“Young Henrys is the type of company that takes leadership in the sustainability space; this partnership between UTS Climate Change Cluster (C3) and an industry leader allows us to showcase that it is possible to have action today on climate change,” adds Professor Peter Ralph, executive director of C3.

“This project really showcases how research together with industry, can create practical and innovative solutions to address global problems today.”